World Bee Populations - Is It A Miracle? GOOGLE IT.

- Get link

- X

- Other Apps

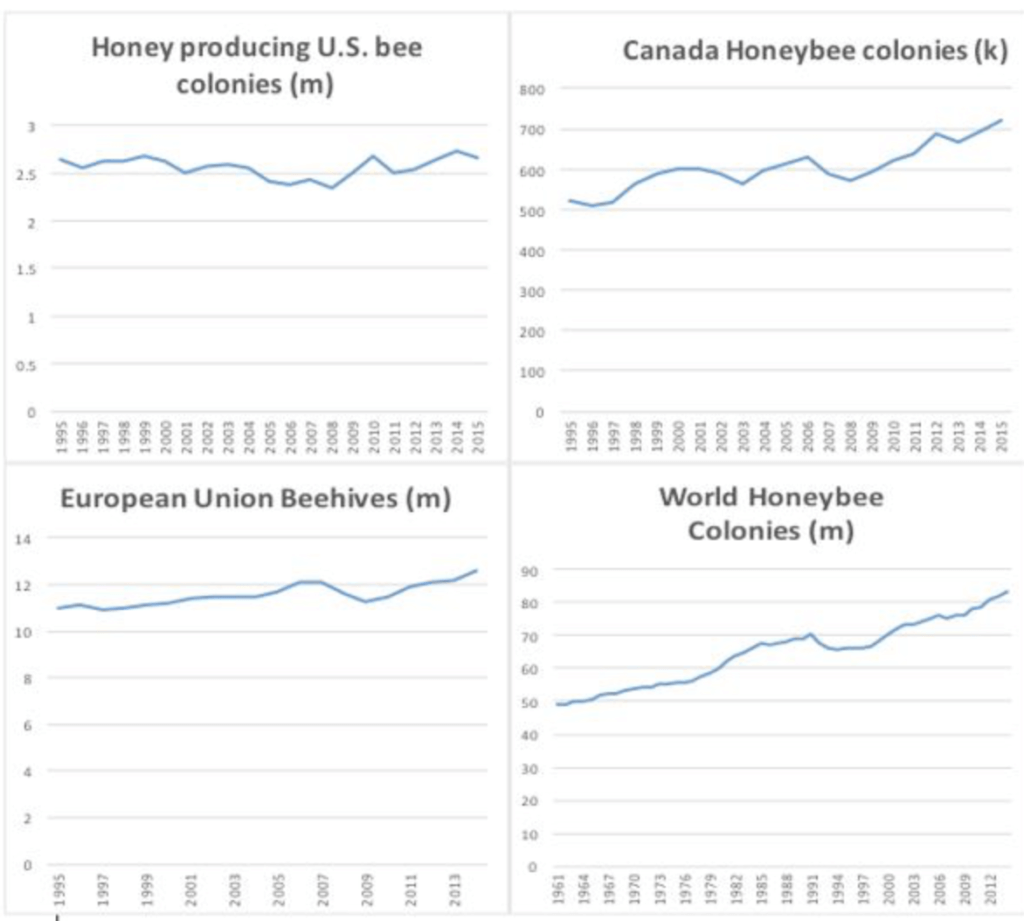

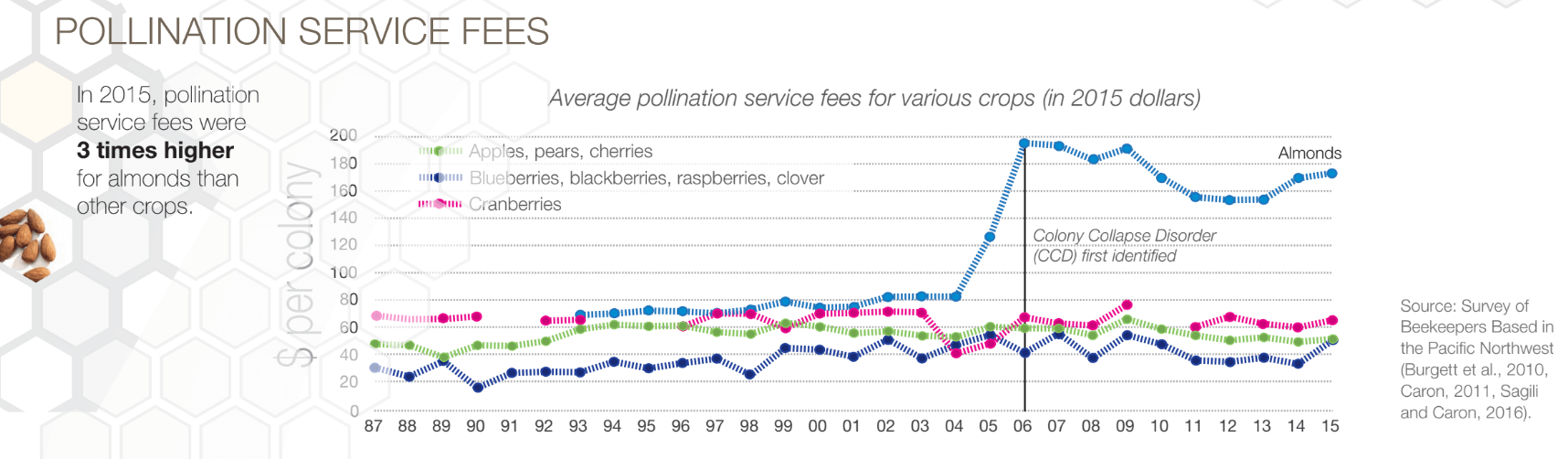

The overall population of honeybees in the US, Canada and Europe has held steady or increased slightly since the widespread adoption of neonics in the 1990s. The US honeybee population hit a 22-year high in 2016, according to the figures released by the USDA before dipping slightly last year, and globally are at an all-time high.

So what’s behind the popular meme of the honeybee, legs pointing to the sky? As often happens in discussing controversial issues such as food and chemicals, it’s complicated––and in part ideological.

chemicals, it’s complicated––and in part ideological.

chemicals, it’s complicated––and in part ideological.

chemicals, it’s complicated––and in part ideological.

First of all, honeybees aren’t the cute symbol of the natural world that environmentalists make them out to be. They’re actually a managed species, like livestock, bred by beekeepers to make honey and shipped around the country to pollinate crops like almonds. They’re also an exotic species in North America, brought over from Europe by early colonists. [Note: European honeybees originated in Asia 300,000 years ago.]

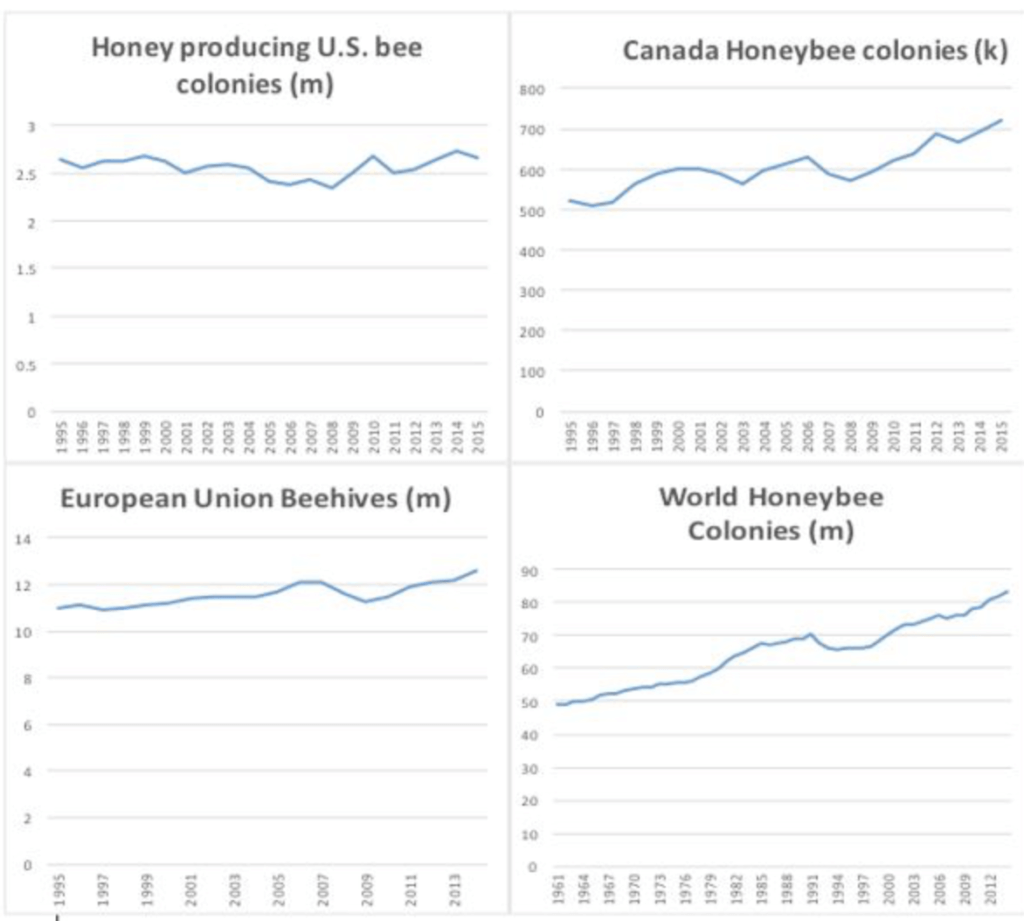

It’s not that honeybees are not facing health challenges — they are. Just not to the degree that environmental groups and the media suggest and not for the reasons popularized by protestors in yellow bee suits. Most of the problems, say entomologists and bee keepers, are linked to bee keeping practices, Varroa destructor mites (which vector roughly a dozen different diseases into beehives), and the widely prevalent gut fungus Nosema ceranae. Seed pesticides, most experts say, play a minor if measurable role, with the miticides used to control the parasites presenting far more of a health threat than neonics. These problems have led to higher-than-average over winter losses. While beekeepers always lose some of their bees over the winter, winter losses of managed honey bee colonies in the US have averaged 28.7 percent since 2006, almost double the historical rate.

So what’s going on? How is the US honeybee population stable or rising despite a doubling of winter loss rates?

Colony Collapse Disorder is not the same as bee losses linked to diseases and chemicals

The independent Bee Informed Partership, which was founded by a grant from the US Department of Agriculture, reported that despite bee health problems in recent years, trends are favorable in tracking overwinter losses, considered the key statistic in evaluating bee colony health.

According to a recent USDA report on honeybee health, beekeepers have been able to adapt their managerial practices and repopulate their stocks when cold weather or virus-related losses occur. Winter losses can easily be replenished by splitting hives, but experts say that’s not the optimal solution; it would be better for bee stocks for overwinter losses to continue their recent decline.

According to a recent USDA report on honeybee health, beekeepers have been able to adapt their managerial practices and repopulate their stocks when cold weather or virus-related losses occur. Winter losses can easily be replenished by splitting hives, but experts say that’s not the optimal solution; it would be better for bee stocks for overwinter losses to continue their recent decline.

“The media have overstressed the mortality aspects and largely ignored the fact that the beekeeping industry is able to rebound,” Michael Burgett, professor emeritus of entomology at Oregon State University and a co-author of the report, told the GLP. “The honey bee is in no way endangered.”

Burgett has been studying bees since 1969, and has noticed a significant uptick in public interest in, and funding for, honeybee research since the onset of “Colony Collapse Disorder” first raised eyebrows when it appeared in California in 2006.

“As a practicing academic for the last 49 years, I’m always delighted when more money becomes available to do research and outreach programs,” Burgett said. “However, it’s based on the falsehood that our honeybee industry is on the decline.”

CCD, which lasted for about 3-5 years, is a sudden phenomenon in which the majority of worker bees mysteriously disappear. That problem, which showed up most dramatically in California, abated by 2011. But reporters continue to use the term, erroneously, to describe other health challenges faced by bees since then, including the growing threat of mite infestations.

High prices are the solution to their own problem

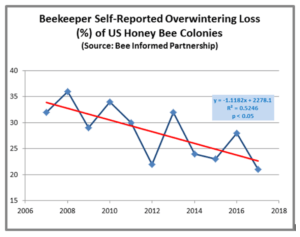

The latest USDA report credits the market for crop pollination services as a key reason why, quoting the old adage, “high prices are the solution to their own problem.”

When winter bee loss rates increased in the mid-2000s mostly as a result of the temporary CCD threat, beekeepers’ bottom line was hurt. This incentivized them to replace their lost colonies and to move their “livestock” to farms that offered better rates. Beekeepers offset the higher winter losses primarily through a process called “splitting.” Splitting involves taking a portion of the eggs, larvae, pupae, adult bees and food stores from a healthy colony and creating a separate colony with a newly mated queen. During spring, both colonies will grow, replenishing the beekeepers’ stocks.

At the same time, pollination fees (mostly for California’s booming almond industry) and honey prices have increased in recent years, boosting the profitability of beekeeping and further incentivizing beekeepers to replace lost colonies. In 1988, honey sales accounted for 52 percent of beekeeper revenue while pollinator service fees made up less than 11 percent. Today, pollination service fees make up over 41 percent, the largest source of beekeeper revenue. Of that, 82 percent comes from almonds.

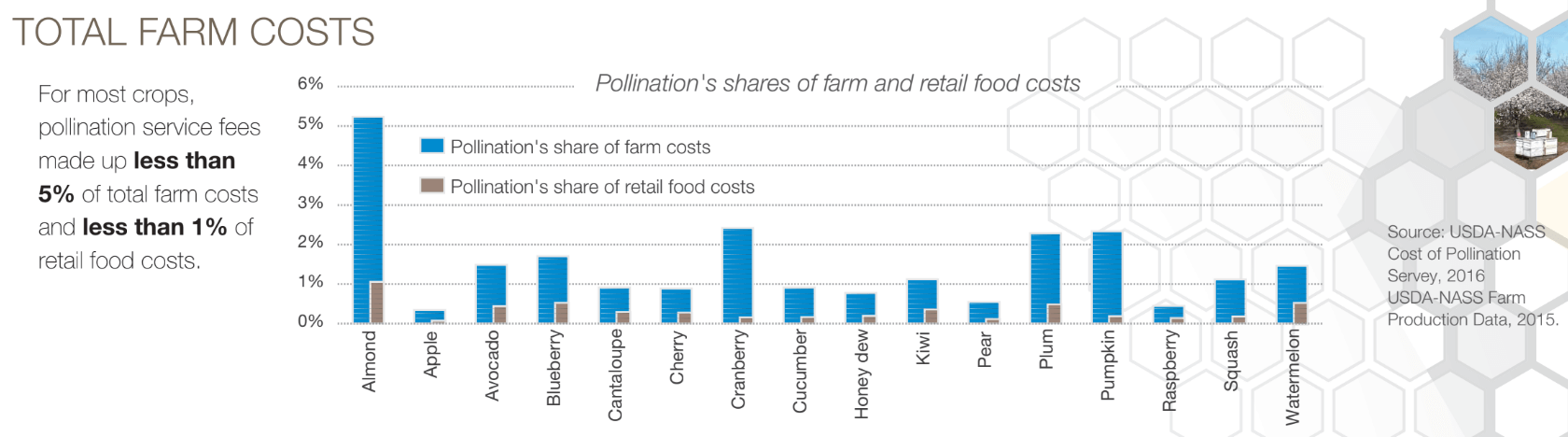

Aside from beekeepers ability to repopulate their colonies and move to fields that pay the highest rates, a third factor that has contributed to the US honeybee population’s stability is the fact that pollinator services make up a small percentage of total farm costs. While pollination services account for a little over five percent of the total cost of growing almonds, no other crop tops 3 percent. And when you consider what the product is sold for in grocery stores, it’s even less, with pollination services for all crops (including almonds) making up just 1 percent or less of retail food costs. This means that pollination service cost increases don’t have a large impact on farmers’ costs or food prices.

USDA bee researcher: “If there’s a top ten list of what’s killing honey bee colonies, I’d put pesticides at number 11.”

While it’s great that beekeepers are able to rebound from increased loses, “it’s not fun having a lot of dead bees,” says Burgett. High loss rates mean more work and costs for beekeepers.

He says the cause of the increased loss numbers are multifactorial, but that varroa mites and the viruses they carry are likely the leading drivers. Nutrition is another big factor. With many colonies being transported to California’s almond groves for pollination, the bees’ diet isn’t very diverse. Burgett says bees need more than just almond pollen to stay healthy.

In the last five years, concerns over Colony Collapse Disorder have eased considerably. Surveys have shown that beekeepers only attribute around 20 percent of their losses to CCD, says Burgett.

And while still an issue, he says pesticides including neonics have become much less of a hazard in recent decades, and doesn’t see them as playing a significant role in the recent increase in losses.

“If there’s a top ten list of what’s killing honey bee colonies, I’d put pesticides at number 11” [not even on the list], he said.

When Burgett first came to Oregon State University, beekeepers would often tell him that pesticides were their number one issue. But things have improved significantly in the decades since.

“The agricultural industry has gotten much, much better,” he explained. “The pesticides we’re using have changed a lot from 30, 40 years ago to generally safer products for honeybees.”

As for neonicotinoids, the controversial class of insecticides commonly applied as a seed coating, Burgett says that despite over a decade of study, it’s still yet to be proven that they’re playing a significant role in honeybee deaths.

But you rarely find that kind of nuanced reporting in the general media or even among the farm press. The anti-chemical meme targeting neonics with the not-all-that vulnerable honeybee as their symbol remains a powerful fund-raising tool for environmental advocacy groups, and is often linked to the organic industry.

Jon Entine is the founder and executive director of the GLP. Follow him on Twitter @jonentine

- Get link

- X

- Other Apps

Comments

Post a Comment